The Changing Metis Identity

The Metis was a group and identity that transformed during the nineteenth century. During this period they went from a divided, polygeneous group to a more unified, homogenous group. Certain atrocities the Metis people faced shaped this identity from the Battle of Seven Oaks and through the racial discrimination they faced from the rest of pre-confederation Canada. This paper will focus, firstly, on the emergence of the Metis in the Red River settlement, as well as the Saint-Laurent and how they were not a group in unison. Secondly, the battle and effects the Battle of Seven Oaks had on Metis identity will be discussed and how this event moved the Metis towards a unified identity. Lastly, “The Declaration of the People’s of Rupert’s Land and the North-West” will be used to understand the mistreatment the Metis faced before confederation and how it lead to this document unifying the group officially in Canada. The Metis were not unified upon its emergence but as the nineteenth century went forward so did their identity.

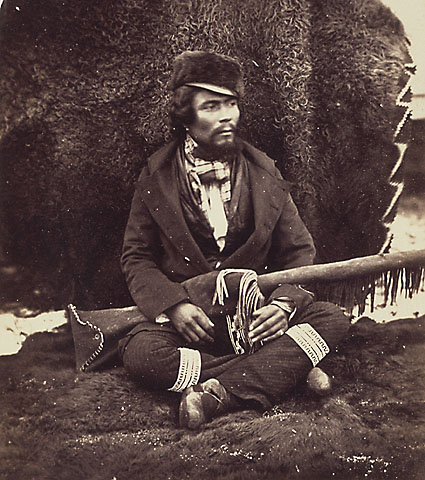

Upon the emergence of this new Metis identity, formed by French or European trappers marrying Indigenous women, was not homogenous. The two major Metis settlements were Red River and Saint-Laurent. These two while similar in heritage were not similar in life. Nicole St-Onge article “Variations in Red River: The Traders and Freemen Metis of Saint-Laurent, Manitoba” mentions how Hudson Bay Company employee Donald Gunn saw the “run-down collection of tents and houses set up in haphazard fashion” and noted the lack of infrastructure. He did not recognized that these Freemen of Saint-Laurent were the same as the Metis in Red River. Due to this he saw these people as ‘Indian’ and noted how the people did not farm[1] This account gives a basis for how even being of the same “identity” they were not the same people with the same ideas. The Metis of Saint-Laurent were viewed as more “Indian” than those of Red River. This is only furthered reinforced when St-Onge notes how “Many members, mostly men but occasionally women, married into the Saulteaux population and several were viewed by local religious authorities as primarily speakers of an ‘Indian’ language.”[2] Unlike the French speaking Catholics of Red River the Freemen Metis of the North-West were once again viewed as more “Indian” due to their cultural practices. This idea of being “Indian” created racial tensions that fueled the “Declaration of Rupert’s Land and the North-West” but it is important to note that at this point the two cultures were not similar. Yet as time went on, and tensions rise these two different cultures had to form one unified identity.

In 1816, a group of Metis and North West Company attacked a group of Scottish Settlers and members of the Hudson Bay Company. The reasons for the battle can be traced back several years and was due to racialization of Metis people, and discriminatory policies directed towards them. The Battle had many effects on Metis people, and their identity. Michael Hughes quotes Arthur Morton and Gerald Friesen in his article, “Within the Grasp of Company Law: Land, Legitimacy, and the Racialization of the Métis, 1815–1821” that the “‘Battle of Seven Oaks triggered the rise of a new Metis nationalism’ and ‘Seven Oaks represents the Metis ordeal by fire that gave them a sense of nationhood that was to be reinforced by Riel and Dumont later in the century’”.[3] This is valuable insight as The Battle of Seven Oaks created this nationalism therefore creating a form of unified identity. Adam Gaudry also supports this feeling of nationalism in his article, “Communing with the Dead: The ‘New Metis’ when he notes

The infinity flag was first unfurled before the Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816, when Métis defeated a group of Hudson’s Bay Company men at Red River. The flag has occupied a central place in Métis identity ever since. It had a place at the head of the old buffalo hunt caravans and today is used as the Métis national flag. It is also featured in each of the logos of the Métis National Council and its provincial affiliates. As the most identifiable symbol of Métis identity, even if it is a nationalist symbol, the infinity flag has been regularly adopted by “new Métis” organizations in their logos, even when few of their ancestors would have used it in its original historical context.[4]

After the battle and the emergence of this new flag that represents all Metis people. This is significant at the time as once again it further supports the Metis move towards a homogeneous identity and bringing the whole group together under one banner. This allows them, and the rest of pre-confederation Canada to recognize they are a legitimate group, and will later allow them to legitimize their identity within Canada.

With the differences discussed previously it is now very possible that all Metis people began to see themselves as one whole group. With this nationalism comes “forceful political assertions that they should be recognized as indigenous peoples with rights to land around Red River”.[5] By fighting politically for the land around Red River and other areas shows how this once polygeneous group is moving towards a homogeneous group. This fight for land also leads into the want for sovereignty that Riel fought for with Canada in later in the century. They felt an ownership to the land they lived on and the Battle of Seven Oaks represents that fight for control. The Metis were defending their own access to resources and hunting grounds that they have used for many years from these new European settlers. Hughes notes how the Metis were constantly referred to as half-breeds and highlights the “growing British and American obsession with classification systems that placed ‘races’ on a continuum of humanity, stretching from savage to civilized”.[6] This is important as many policies and attitudes reflect this assumption of Metis people as half-breeds and savages in need of rescuing and to undermine their identity by making them “inferior”. Racial issues are hard to ignore as some of Riel and Bruce’s demands to the Canadian government alluded to this racial tension placed by European settlers and policy makers. This racial tension can be seen in a publication that stated

an impression is attempted to be made, that these latter people are a race only known since the establishment of the North-West Company; but the fact is, that when the Traders first penetrated into that country, after the conquest of Canada, they found it overrun by persons of this description, some of whom were the chief Leaders of the different Tribes of Indians in the Plains, and inherited the names of their Fathers, who had been the principal French Commandants, and Traders of the District.[7]

The author is noting how these “made up” people (the half-breed Metis) took over settlements in the Prairies and took it over in the name of the French. This was an attempt by the Hudson Bay Company to displace these land rights the Metis were fighting for. This English company was using their indigenous heritage, and French way of life to undermine the rights these people should possess. The Hudson Bay Company refused the acknowledge the Metis as indigenous people entitled to land rights, and could not view them as equals as they were French. This publication and attitude only furthered the Metis nationalism and once again lead the way to “The Declaration of the Peoples of Rupert’s Land and the North-West”. Their indigenous heritage should give them entitlement to the land they live on and this attitude that they have no entitlement because of their half-breed status was the cause for a battle of sovereignty. The Battle of Seven Oaks encompassed all of these issues relating to land rights and the protection of those rights. It created a new sense of nationalism and identity for Metis people, and it highlighted the racial discrimination they faced by English people especially. All of these issues will be brought up later in Riel, and Bruce’s declaration.

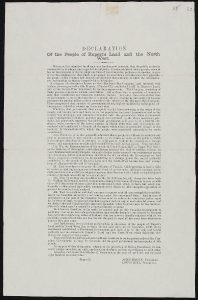

“The Declaration of the Peoples of Rupert’s Land and the North-West” was a document on December 8th, 1869 by Louis Riel and John Bruce. As aforementioned the Metis were subjugated to racism in politics and by the English in particular. They also dealt with the issue of land rights and defence of that land as the Battle of Seven Oaks showed. The four demands Bruce and Riel outlined that highlight the issues the Metis have faced thus far. Firstly, the want for freedom from the Canadian government can be seen in the treatment the Metis received. Through Hudson Bay Company attitudes of racism and their attempts to undermine their indigenous heritage it makes sense as to why this was demanded. By leaving from the control of the government they should reclaim that land right they have to the land. This also allows them to create their own self governing society with the values and norms Metis people have versus those imposed by a federal government. This demand shows a real homogeneous identity or at least the need for one. The second demand states a refusal to “recognize the authority of Canada, which pretends to have a right to coerce us…”[8] This can certainly relate to policies directed at limiting Metis people. With policies such as the Pemmican Proclamation meant to disrupt trade and the economy of the Red River Metis, and the Hudson Bay Company attempting to undermine the land rights of the Metis to the current government means that the Metis had to refuse the authority of any later government. These practices and policies attacked the Metis culturally, economically and politically attempting to show they had no power in any regard against the government. So Bruce and Riel’s demand to refuse the Canadian government was built upon a history of mistreatment. Thirdly, they demanded William McDougall be driven away from the area. This may seem like a small demand but once again is built upon history. The last time white settlers came into Metis territory was with Lord Selkirk and the result was these settlers taking over traditional Metis hunting and fishing grounds. They also faced racial discrimination being denoted as half-breeds. These reasons were the basis for the Battle of Seven Oaks, so it is justifiable why McDougall should be driven away from Metis territory. Lastly, they state that the Metis will “continue to oppose with all our strength the establishing of the Canadian authority in our country under the announced form.”[9] This simply reiterates things previously mentioned but the language is what really makes this document the final act of legitimizing Metis identity. This land is ‘our’ land and they will oppose with all ‘our’ strength. This document legitimizes that the Metis are one whole, homogeneous group within Canada. With all the atrocities the Metis faced by English and sometimes French settlers they had to strengthen themselves through violence, rebellion and by finally creating a true identity for themselves.

“The Declaration of the Peoples of Rupert’s Land and the North-West” was a document on December 8th, 1869 by Louis Riel and John Bruce. As aforementioned the Metis were subjugated to racism in politics and by the English in particular. They also dealt with the issue of land rights and defence of that land as the Battle of Seven Oaks showed. The four demands Bruce and Riel outlined that highlight the issues the Metis have faced thus far. Firstly, the want for freedom from the Canadian government can be seen in the treatment the Metis received. Through Hudson Bay Company attitudes of racism and their attempts to undermine their indigenous heritage it makes sense as to why this was demanded. By leaving from the control of the government they should reclaim that land right they have to the land. This also allows them to create their own self governing society with the values and norms Metis people have versus those imposed by a federal government. This demand shows a real homogeneous identity or at least the need for one. The second demand states a refusal to “recognize the authority of Canada, which pretends to have a right to coerce us…”[8] This can certainly relate to policies directed at limiting Metis people. With policies such as the Pemmican Proclamation meant to disrupt trade and the economy of the Red River Metis, and the Hudson Bay Company attempting to undermine the land rights of the Metis to the current government means that the Metis had to refuse the authority of any later government. These practices and policies attacked the Metis culturally, economically and politically attempting to show they had no power in any regard against the government. So Bruce and Riel’s demand to refuse the Canadian government was built upon a history of mistreatment. Thirdly, they demanded William McDougall be driven away from the area. This may seem like a small demand but once again is built upon history. The last time white settlers came into Metis territory was with Lord Selkirk and the result was these settlers taking over traditional Metis hunting and fishing grounds. They also faced racial discrimination being denoted as half-breeds. These reasons were the basis for the Battle of Seven Oaks, so it is justifiable why McDougall should be driven away from Metis territory. Lastly, they state that the Metis will “continue to oppose with all our strength the establishing of the Canadian authority in our country under the announced form.”[9] This simply reiterates things previously mentioned but the language is what really makes this document the final act of legitimizing Metis identity. This land is ‘our’ land and they will oppose with all ‘our’ strength. This document legitimizes that the Metis are one whole, homogeneous group within Canada. With all the atrocities the Metis faced by English and sometimes French settlers they had to strengthen themselves through violence, rebellion and by finally creating a true identity for themselves.

Throughout the history of the Metis many atrocities were placed upon them politically, culturally and socially. Racial discrimination, aggressive policies, and undermining of their legitimate heritage caused a once polygeneous group of people with different cultural aspects become homogeneous. Events such as the Battle of Seven Oaks caused a rise in nationalistic ideas, and it created a flag that the Metis would recognize themselves under. This act was the first big step towards becoming unified. The racial discrimination they faced by being call half-breeds would only further support their need to be unified as no matter how different they were culturally European settlers saw them all as inferior. The Hudson Bay Company’s attempt at removing Metis land rights due to their heritage also showed the Metis a need to unify and suppress these attempts otherwise they would lose what belonged to them. The battle also showed these people that they in fact did have power to fight back against such attempts. Lastly, Bruce and Riel’s declaration to the Canadian government highlight all of the issues the Metis had been subjugated to and legitimized in writing the Metis identity. It was this final act that truly made this Metis identity real and homogeneous identity for all the people included.

Bibliography

Bruce, John. Riel, Louis. Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land and the North-West, December 1869.

Gaudry, Adam. “Communing with the Dead: The ‘New Metis,’ Metis Identity Appropriation, and the Displacement of Living Metis Culture.” American Indian Quarterly 42, no. 2 (May 2018): 162-90

Hughes, Michael. “Within the Grasp of Company Law: Land, Legitimacy, and the Racialization of the Métis, 1815-1821.” Ethnohistory 63, no. 3 (July 2016): 519–40

St-Onge, Nicole J.M. “Variations in Red River: The Traders and Freemen Metis of Saint- Laurent, Manitoba.” Canadian Eithnic Studies 24, no. 2 (June 1992).

Wilcocke, Samuel, A Narrative of Occurrences in the Indian Countries of North America, since the Connexion of the Right Hon. The Earl of Selkirk with the Hudson’s Bay Company, and His Attempt to Establish a Colony on the Red River; with a Detailed Account of His Lordship’s Military Expedition to, and Subsequent Proceedings at Fort William, in Upper Canada. London: McMillan. 1817.

[1] Nicole St-Onge, “Variations in Red River: The Traders and Freemen of Saint-Laurent, Manitoba”, Canadian Ethnic Studies 24, no. 2 (June 1992)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Michael Hughes, “Within the Grasp of Company Law: Land, Legitimacy, and the Racialization of the Métis, 1815-1821.” Ethnohistory 63, no. 3 (July 2016).

[4] Adam Gaudry, “Communing with the Dead: The ‘New Metis,’ Metis Identity Appropriation, and the Displacement of Living Metis Culture.” American Indian Quarterly 42, no. 2 (May 2018).

[5] Hughes, “Within the Grasps of Company Law”, 522.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Samuel Wilcocke, A Narrative of Occurrences in the Indian Countries of North America, since the Connexion of the Right Hon. The Earl of Selkirk with the Hudson’s Bay Company, and His Attempt to Establish a Colony on the Red River; with a Detailed Account of His Lordship’s Military Expedition to, and Subsequent Proceedings at Fort William, in Upper Canada. London: McMillan. 1817.

[8] John Bruce, Louis Riel, Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land and the North-West, December 1869.

[9] Ibid.